|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Instrument Reviews

CD & Book Reviews

|

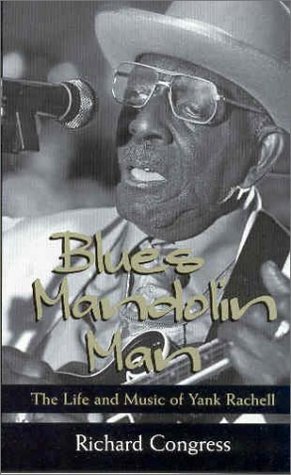

Blues Mandolin Man: The Life and Music of Yank Rachell

Richard Congress

Born in Brownsville, Tennessee, in 1910,

James "Yank" Rachell

was one of the few prewar blues recording artists to continue

performing into the 1990s, and the only such artist whose primary

instrument was the mandolin. For most of his life, Rachell was

not a full-time musician; he settled in Indianapolis and worked

day jobs to support his family. This decision, coupled with

his choice of instrument, meant that Rachell spent his whole

career in Almost Complete Obscurity. But after all, that's what

we specialize in here at emando.com.

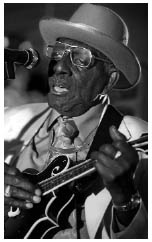

Blues Mandolin Man, the first biography of Yank (and there won't likely be many others), is the work of Richard Congress, the owner of Random Chance Records, the New York label that reissued two of Yank's albums, Yank Rachell and Blues Mandolin Man, on CD in 1999. The first 22 chapters—roughly half of the book—are transcripts of interviews that Congress conducted and taped during the last few months of Yank's life. Congress has arranged the material into rough chronological and thematic order, but otherwise provides no framing or narrative structure for Yank's yarns—although he does chime in with an occasional footnote when he thinks Yank is either mistaken or pulling the interviewer's leg. It's nice to read the whole cloth of Yank's recollections about growing up in Brownsville, the musicians he played with, and the trouble they got into. He holds forth on everything from his first mandolin to racial strife in his hometown to rap music. If you want a nice, neat, timeline-driven package of information with all loose ends accounted for, this isn't it. You just might go nuts trying to figure out how many jobs Yank's father worked or how many years Yank spent playing with Sleepy John Estes. On the other hand, as an example of an old-time bluesman telling his own story in his own way, this first section of the book is invaluable. Five appendices constitute the remainder of the book, and they prove just as interesting as the transcripts. We get detailed comments on Yank's mandolin and guitar styles from Rich Del Grosso and David Evans, respectively; a series of enlightening interviews with musicians, concert promoters, and record label owners who knew and worked with Yank or were influenced by him; biographical notes about all the musicians Yank mentions in the transcripts; and newspaper articles about the lynching that convinced Yank to leave Brownsville for good. There's also an excruciatingly detailed discography and a good selection of song lyrics. Yank was known primarily as a player of "rural" or "country" blues. To most people this means "acoustic," but not necessarily to Yank. He preferred to plug in, possibly because it put his mandolin on an equal footing with the rest of the band without his having to play too hard. He tells Congress in Chapter 21: "When electric come in, that was something new to me, so I played that. I plugged my mandolin up into it. It sound good, so I went to playing electric all the time, you know. ... I like that Chicago Style better than I do any of 'em. Chicago Style is electric, and I could play the mandolin better with electric. You ain't got to blast and play loud with electric."  photo: Patrick Schneider, courtesy of the Indianapolis Star

Yank also reveals that playing acoustically on his last

recording session (which resulted in the Too Hot for the

Devil CD on Flat Rock Records) was the producers' idea,

not his. Nothing in the book indicates when Yank first started

to play plugged, or when he acquired the

Harmony Baroque electric

mandolin that served as his main instrument in later life. One

other tantalizing tidbit: The book's cover photo clearly shows

Yank playing the Flatiron acoustic procured for him by the Lovin'

Spoonful's John Sebastian. Inside the book, facing the title

page, the same photo appears—only this time (as you can see

here) it's cropped differently, and lo and behold, the Flatiron

has been fitted with a

DeArmond pickup. This probably won't matter to anyone but

me, but I was happy to see it.

Buy Blues Mandolin Man at Amazon.com

Overall:

|